In the last few days, the Easter messages of the Christian churches in particular have repeatedly pointed out the desolate state of the world and the many political crises. Were these just generalities that go particularly well with the Easter messages? The MBI CONIAS data confirm: We are currently living in a special global crisis situation. Never before has the number of wars and current conflicts been so high. More details can be found in this article.

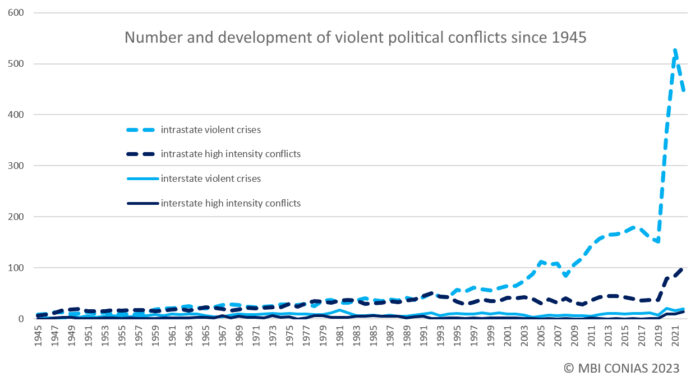

The updated CONIAS graph shows the overall development of conflicts since 1945, making it clear at first glance that we are in a particularly exceptional situation, especially when compared to the 1950s to 1970s. The graph clearly illustrates that the number of violent conflicts has increased tenfold in some cases over the decades - especially that of domestic conflicts below the threshold of war (typically terrorist attacks, rebel actions, but also riots at demonstrations).

Number and development of violent political conflicts since 1945

When discussing this graph in presentations and seminars, it is often assumed that the progression of the graphs reflects the availability of information resources rather than actual political developments. The assumption is more than justified given the influence of the internet, its diverse sources of information, and the resulting possibility to now obtain information on political conflicts from every corner of the globe, sometimes even in real-time. Indeed, we now have processed data from organizations at our disposal that have a wide network of local reporters and can report even from regions where no journalist would otherwise dare to go. These almost unknown conflicts – if they actually existed in the 1950s – are not recorded in any conflict statistics.

Change in the international system creates room for political conflict

Nevertheless, it would be completely insufficient to attribute the increase in political conflicts solely to the internet and new sources of information. This view alone would completely neglect the fact that in the past 75 years of conflict monitoring, the international system has changed more than once, and this change has created new spaces and opportunities for political conflict.

This became most obvious at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s: The end of the East-West conflict also meant an end to the bipolar situation and an end to massive financial and military support for intrinsically weak states in order to draw them into the respective camps. The reduction of these sometimes massive payments to foreign governments meant that states could no longer finance their armies. Thus, rebel groups with much simpler weapons, but high motivation saw the opportunity to implement their demands or idea of politics – perhaps only in parts of the state – through the use of violence.

The attacks of 9/11/2001 can also be identified as such an epochal event, as the subsequent military actions in Afghanistan and Iraq gave rise to the creation of a multitude of new religiously motivated groups and created a new kind of threat in some parts of the world. Similarly, then-U.S. President Trump's announcement in 2019 that the United States no longer saw itself in the role of "world policeman" created space for a variety of new conflicts, predominantly at the level of interstate conflicts.

Security as an inflationary term: Changes in the understanding of security

In addition to the two reasons mentioned above, there is another, very decisive factor that explains the increase in violent conflicts, especially below the threshold of war: The understanding of security has changed greatly over the decades in connection with a rapidly growing globalization, with a fundamental increase in world trade and with an almost unmanageable number of interlinked supply chains. While in the years of the Cold War, in view of the nuclear threat, the interest of (quantitative) conflict research was mainly focused on the risk of interstate war, its origin, frequency and duration, today security has become an almost inflationary term. Today, security and its associated risks are rarely applied to "national security" or "security of one's own state's borders"; rather, in the course of the interconnected global economy, security issues relate primarily to security of the supply chain, production, transportation and logistics, as well as real estate and tourism destinations.

This broadening of security issues almost inevitably leads to an expansion of the political conflicts that can be observed. To paraphrase a well-known comparison in risk research: In the 1960s and 1970s, the security threat was thought to come almost exclusively from the interstate nuclear threat. In terms of early risk identification, attempts were made to discover those diplomatic and other interstate tensions and conflicts that past investigations showed could develop into wars. Today, we know that a self-immolation of a single vegetable vendor, regrettable for outsiders but not newsworthy in itself, can lead to the domestic conflagration of entire regions – see the events of the Arab Spring.

This can be compared to a researcher who assumes for years that all swans are white and that he can therefore neglect all duck birds with a different color. When he learns that there are also black swans, he has to change his focus. Likewise, quantitative conflict research today knows that there are a multitude of different starting points for security risks. Not all of them will always end in war and destruction, in terror and violence, but they must be monitored and analyzed. This fact also explains the increase in violent conflicts. Today, we no longer see only white and black swans, but a variety of new shades. The recorded rise in violent political conflicts is therefore due in no small measure to a changed need for security.

Excluded from this consideration is the number and development in the category "wars". Here, the definition criteria are tougher and higher than for other violent political conflicts and are therefore applicable over the entire period under review. The visible increase in the number of wars therefore confirms the initial thesis: We are indeed in a phase with an extremely high number of political crises.

If you would like to learn more about political crises and the associated risks for your company, feel free to sign up for our MBI CONIAS Academy or contact our team of experts.

About the author:

Dr. Nicolas Schwank

Chief Data Scientist Political Risk

CONIAS Risk Intelligence

Michael Bauer International GmbH