Politically, South Africa is one of the most stable democracies in Sub-Saharan Africa. The GDP of US$ 295.5 billion makes South Africa the second-largest economy on the Sub-Saharan continent, only outperformed by Nigeria. After years of political stagnation associated with economic slowdown, it appears that a mood of awakening currently prevails in the country: Last month, African National Congress (ANC) decided to withdraw then-President Jacob Zuma from his position, after he had refused to recede. ANC chairman Cyril Ramaphosa, former Deputy President, civil rights activist, union leader and businessman succeeded him.

Hence, the question arises what the change of government will mean for South Africa being a strategically crucial country in general and in particular for Sub-Sahara Africa, due to is geographic location and its economic significance?

The transition of power is highly noteworthy since the ANC is actually known for its party and hierarchical discipline that, in the past, helped Zuma to survive eight votes of no confidence in total. Furthermore, its occurrence is accompanied by a remarkable phase of political détente:

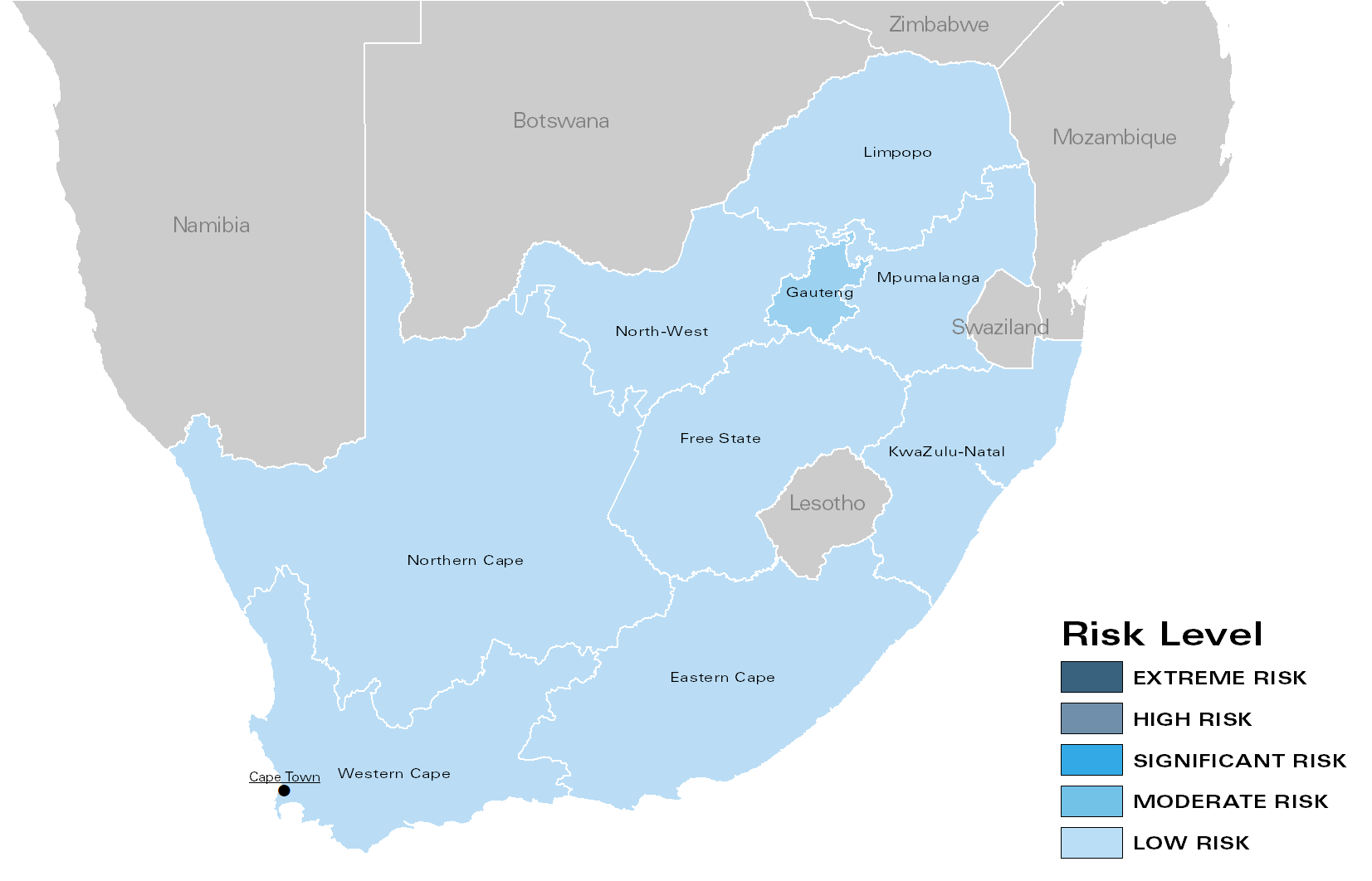

Fig. 1: Regional Risk Levels for South Africa (opposition) in February 2018

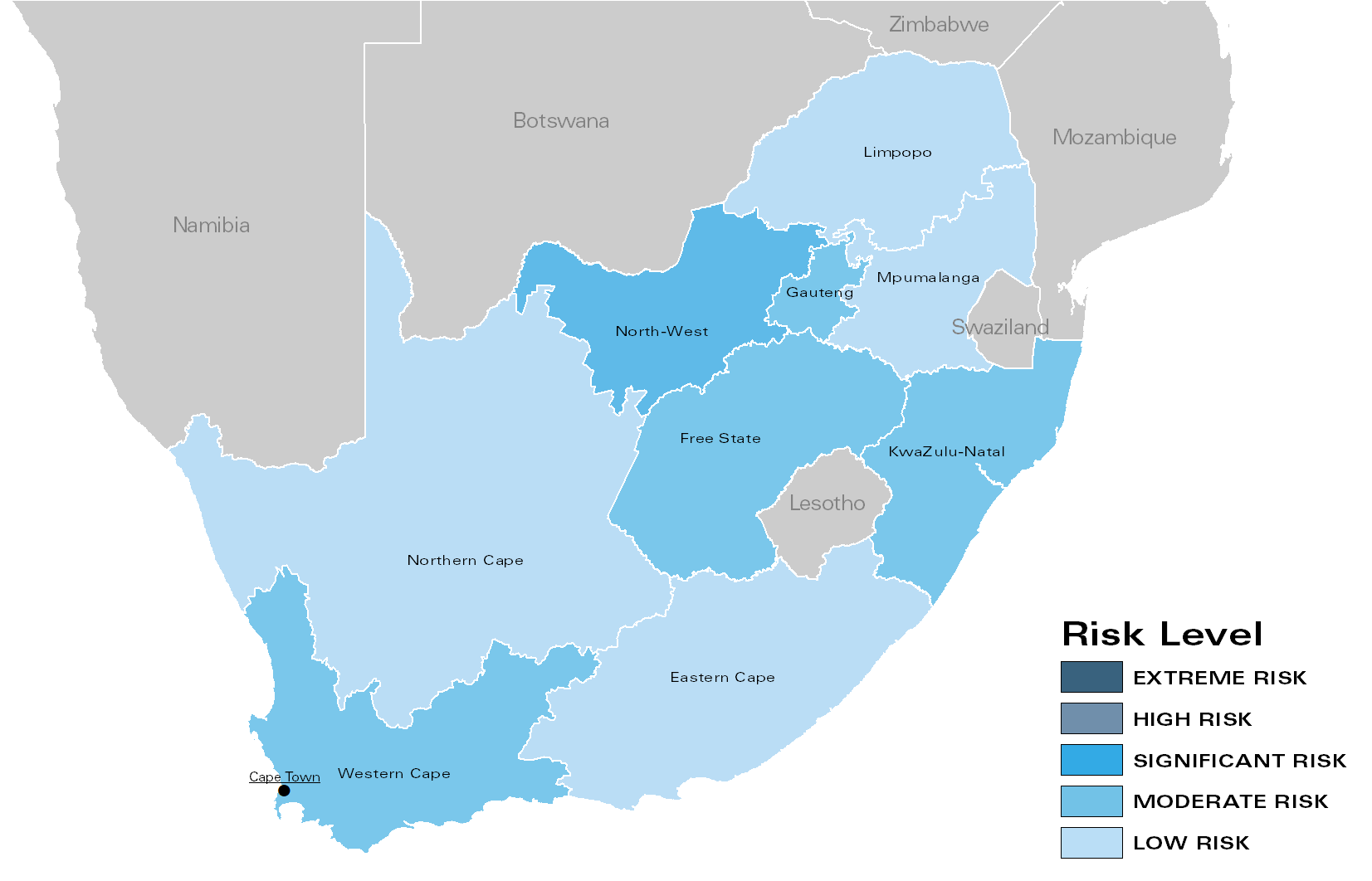

Fig. 2: Regional Risk Levels for South Africa in February 2018 (all conflicts)

Although in one case Zuma supporters clashed with the police in Johannesburg (Gauteng), the transfer of power in form of a forced resignation was quite peaceful (s. fig. 1) compared to the outrages and incidents regularly happening on election days. This can be explained by people's obvious weariness of former president Zuma and his involvement in several corruption and money laundering scandals in his two terms that, for instance, even overweights the Zulu tribal solidarity.

Before the personnel change, the conflict over national power between the South African opposition and the ANC, that governed the country since the end of apartheid, reached a peak in 2017: In March, then-President Zuma once again triggered mass protests throughout the whole country, following a midnight cabinet reshuffle in which he dismissed, for instance, popular Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan.

Despite the peaceful transition most recently, Ramaphosa still governs a country with apparent social and structural grievances: Fig. 2 shows that the quietness of the opposition conflict was deceptive since more than half of South Africa’s regions were affected by social conflicts. They materialized in violent acts, protests and confrontations, such as riots targeting the higher education system, immigrants, housing shortage, or service delivery. For a presumptively long time, these topics will also pose a challenge for the new president Ramaphosa.

While his popularity among the population is ambivalent, markets reacted with enthusiasm and optimism to him entering office. Due to him receiving advance praise for his clean reputation and being economic-friendly and reform-driven, he will possibly be granted a brief period of grace which is why it can be expected that there is a short-term improvement for almost all categories’ risk levels listed in the table below (see tab. 1).

Tab. 1: Short-Term Risk Level Trends for South Africa

The smooth and ordered change of government from the discredited former president Zuma to trustworthy businessman Ramaphosa suggests a constant regime stability, as well as a slightly improving situation for business continuity but also for the security of employees in the short run, as the crucial political phase proceeded without widespread national protest and Ramaphosa will likely be given some time to deliver results.

Still, a further outlook into the future is shaped by increased uncertainty: Besides the omni-present social unrest, fresh calls for nationalization of companies operating in the mining and banking sector as well as the parliament’s adoption of a land reform law aiming to amend the constitution and to expropriate Boer farmers, might indicate that, in the worst case, South Africa could take the same road in the long run that led to the Zimbabwean disaster in the early 2000s.