China wants to revive the Silk Road.

What opportunities and risks does this revival present to the international automotive industry?

Many were astonished: for the first time in history of the World Economic Forum in Davos, a leader of a non-capitalist country opened the event with a plea for free trade. During his speech, Xi Jinping, president of the People’s Republic of China, emphasized that he stands for an open and transparent trade system, one that would be able to address refugee crises, political instability, and warlike disputes.

It looked as if Xi wanted to profile himself as an “anti-Trump” more than to present a PR campaign to bring foreign direct investment to China. But in reality, his statements revealed a comprehensive economic and trade strategy. Since 2013, China has focused on expanding trade infrastructure in Eurasia with its “One Belt, One Road” Initiative. Beijing’s commitment is particularly evident in its construction and expansion of new bridges, highways, ports and railways. In 2009, for example, China took over major parts of a port complex in the Greek city of Piraeus, causing a worldwide sensation. It is estimated that China plans to invest €500 million there.

Currently, significant share of world trade transits via Asian sea lanes. In coming years, China also could open up its western borders to use alternative land routes. Contracts worth US$200 billion have been awarded for infrastructure projects. Analysts are convinced, that the sum could quintuple in the next ten years to reach US$1 trillion.

But will China’s effort dictate trade conditions and lead to new dependencies in international trade relations? German companies focused on exporting their goods should pay special attention to these issues now.

With its infrastructure projects, China aims to increase wealth in its western provinces. At the same time, these measures should are meant to address Islamist and separatist movements in the region, not only in Xinjiang and Tibet, but also in some parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan. The multi-ethnic states of Central Asia are affected by social and political conflicts, some of them highly violent and destabilizing across national borders. Though, stability in the Silk Road areas is by no means self-evident. Another goal behind China’s “One Belt, One Road” is strategic: to address geopolitical rivalries in the region by circumventing potential blockades by geopolitical rivals and use the initiative to counteract US hegemony in global trade affairs.

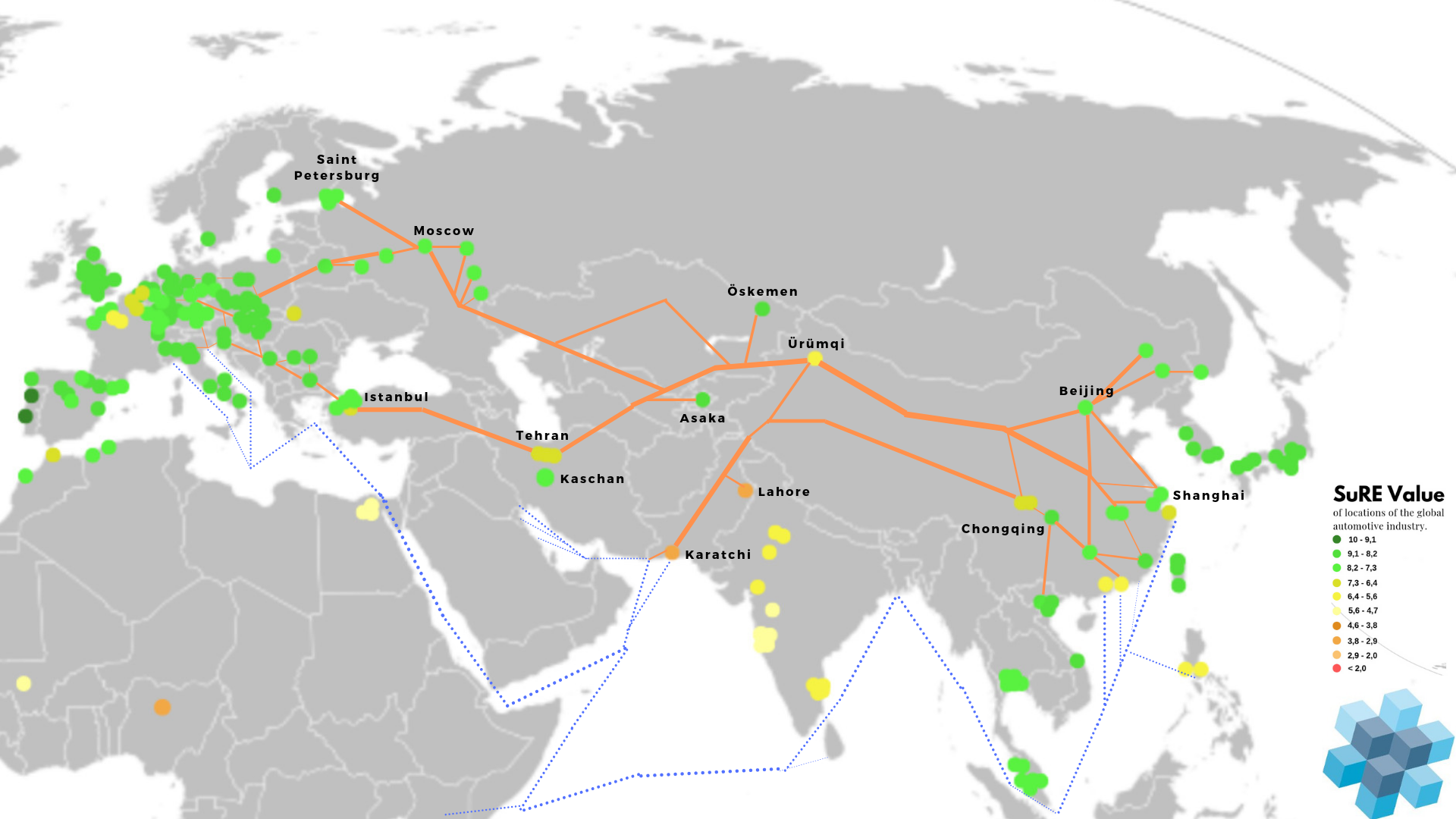

The expansion and strengthening of land-based Central Asian trade routes by China presents not only new opportunities but also challenges to automobile manufacturers. CONIAS research reveals that the Belt is estimated to cover 56 out of 91 production sites in Asia that could be connected directly to the Silk Road land route. The situation is similar in Europe where 98 of 111 locations are in the Belt area.

The following section offers a hot-spot overview about the security situation of selected regions along the Silk Road.

Ürümqi (People’s Republic of China)

The security situation in the region of Chinese city Ürümqi is defined as solid, despite the conflict between Uyghur tribes and Chinese central government. Since 2017, the security situation has improved significantly and the economic environment seems stable. Although the region has political tensions, international companies are setting up shop. Volkswagen, Germany’s only car manufacturer with a location in Central Asia, has a factory in the region. It is estimated that Ürümqi will benefit from Beijing’s growing investments in infrastructure and manufacturing and expand its importance as a logistics and trade center in Central Asia.

Oskemen (Kazakhstan)

Oskemen is the capital of the Kazakh province of East Kazakhstan. Situated in the northeast of the country, the city has a very stable security environment and is connected with highways and railroads to the nationwide transportation system. General Motors and the Czech producer Skoda currently operate in the city. As for the Chinese Silk Road project, additional investment is expected, especially in highways and rail routes to China and Russia. Furthermore, because of its industrial base, the region of Oskemen already has skilled workers. The interdependence between China and Kazakhstan could grow rapidly in coming years as Kazakhstan owns not only tremendous amounts of oil and gas reserves in the Caspian region but also basic raw materials, which are of great interest to Chinese industry. The two countries have established a free trade zone in their border region. On the Chinese side, a city for more than 100,000 inhabitants is already being built. While Chinese officials stress the opportunities for cooperation above all, many Kazakhs are concerned about growing Chinese influence.

Asaka (Uzbekistan)

Located in the center of Central Asia in the Fergana Valley, Asaka has been one of the fastest growing cities in Uzbekistan since the early 1990s. The security situation is stable to good and both the regional market and the export routes to China and Europe make the location attractive to foreign investors. The Uzbek part of the Fergana valley is connected with the rest of the country, including the capital Tashkent, by the Chinese-financed 19.2-kilomenter Kamchiq railway tunnel. In Asaka, GM Uzbekistan – a joint venture between General Motors and an Uzbek state-owned company – produces a variety of mid-class Chevrolet models. The factory is considered the first of its kind in Central Asia. In order to expand local vertical integration, the Uzbek government is pushing ahead with developing a supply industry. One example of this development is the newly founded company GM Powertrain Uzbekistan. Overall, it is expected that the region around Asaka will be further developed with Chinese efforts and investments.

Lahore (Pakistan)

Lahore is the economic center of the northern part of Pakistan. The security situation in the region is tense and has deteriorated since 2017. In addition to internal social conflicts, the relationship between Pakistan and India is very problematic. Traffic jams are also a negative regional phenomenon. While it is expected that geopolitical conflicts between India and Pakistan will persist, Chinese investments could improve the conditions in terms of economic growth. For example, the Chinese plan to construct a 1100-kilometer highway between Lahore and Karatchi, including bridges over the Indus River. The expansion of the Karakorum highway to the Chinese province Xinjiang is also part of the infrastructure package and is expected to contribute to economic growth in Pakistan. If these expectations are met, Pakistan, with its 200 million inhabitants, could be a very attractive market, and not only for Chinese goods. Japanese automotive manufacturer Honda already employs more than 5,000 workers in Lahore.

Karachi (Pakistan)

With more than 17 million inhabitants, Karachi is one of the largest cities in Pakistan. As in Lahore, the level of security has decreased significantly over the past two years. Despite having a good infrastructure, including developed highway systems and a modern airport, the region suffers with ethnic conflicts between the Sindhi people and Urdu immigrants. One advantage Karachi does have is its location on the Indian Ocean. Afghanistan and Pakistan conduct most of their respective sea-based trade via Karachi’s port, making Karachi an international logistics center and attractive for international investments. One important question is whether the port of Gwadar (Beluchistan) could be a serious challenge for Karachi’s economic success, because of Chinese ambitions to make Gwadar their strategic port at its “String of Pearls”. The Indus Motors Company – a joint venture between the Pakstani conglomerate House of Habib and Japanese auto manufacturer Toyota – has been producing automobiles in Karachi since 1990 and employs about 5,000 workers.

Conclusion

China’s New Silk Road is growing and connecting the region and can give new perspectives to the automotive industry in Central Asia. The question is whether Chinese investments are sustainable for regional peace, stability and wealth. Is it possible that new conflicts about the distribution of financial resources could rise? With new roads, bridges, tunnels and factories, the production capacity and import-export options for Central Asian states will increase. However, depending on where you look in the region, the situation is different: while three of the locations discussed here have stable environments that could be made more attractive by the Silk Road, the situation in Pakistan, for example, is increasingly politically tense. As indicated in the 2017 and 2019 SURE Values below, investors who want to benefit form the Silk Road should take these risks into account when entering the market.